[another imagined look back to the twenty first century from some far century, this time looking at the art of film making]

Although it was not recognised at the time, the 2003 film Timecode by Mike Figgis was the harbinger for the style of film making that we now take for granted.

The use of split screen had appeared sporadically before, and the Zbigniew Rybczyński Oscar winning short film Tango certainly played with the notion of repetition within a frame.

However it was only during the 2030’s that entire duration multiple screen films became commonplace. Prior to then consumers had had to create their own personalised multiple screen effect for themselves. Although evidence is inevitably hard to come by, as the quotidian is typically undocumented and unrecorded, it would appear that those who were nominally watching a single screen would routinely, at the same time, employ various other screens to access other entertainment as well as information on the film that they were seeing, engage in electronic conversation with others who were watching, or had watched, the film, as well as, the constant ongoing checking of social media and other data sources.

Clearly the consumer had an appetite for a far greater volume of data and complexity that the film industry was apt to present them with. For consumers, a single narrative thread over a nearly two hour typical duration, without user interactivity or responsiveness was proving increasingly un-engaging and unsatisfying. Consumers were already creating their own workaround for this frustrating shortcoming, so when more immersive filmic experiences were finally available consumer tastes were already surprisingly advanced.

The time had clearly come for the routine presentation of films in a multiple screen format, with at least one strong narrative thread on display at any one time, or at times multiple narrative threads. Consumers proved surprisingly adept at coping with what might previously have been seen as information overload. Techniques such as the classic format of quick slow, quick slow, were used. This offered a quickly paced narrative thread and a slowly paced narrative thread, alongside a more decorative, perhaps repetitive or irrelevant, element that was quickly paced and one that was more slowly paced. In addition there would be multiple areas of running and sporadic text visible. Therefore the consumer always had a myriad of primary and secondary focus options before them. It is not clear whether consumers had always had the capacity and desire to consume this level of data, or whether it was a reflection of the modern way of living whereby it became a commonplace to be constantly connecting, engaging in multiple conversations across multiple social media applications.

Not content with multiple visual screen sectors, consumers wanted a more immersive and challenging filmic environment, one that presented more options, depth and breadth. Interactivity during the film allowed for additional relevant information to be accessed, previously additional commentaries had been provided, but enjoyed relatively little popularity. The new films allowed for a depth of engaging information to be presented during the duration of the film.

Additionally, consumers were already well familiar with algorithms being used to suggest material that they would potentially like, engaging with their established tastes and preferences, while also at times, adding a degree of challenge. It was now possible for film makers to provide multiple narratives, character viewpoints, endings, etc, and for the consumer to be seamlessly presented with the option most likely to engage and amuse them.

It was however clear that the narrative convention and commonality of experience had to be sustained to some degree. So, at initial viewing, the viewer must be able to retain their engagement with the narrative, and not constantly feel that this was being undermined or that key narrative outcomes were being disclosed in advance. In order to be a satisfying filmic or fictional experience it is necessary to be able to immerse yourself in an engaging fiction, and for the key elements of that fiction to be maintained throughout, and amplified by the resolution of the narrative. However this did not require that the same narrative arc was constantly and repetitively deployed, although this was certainly common. Fresh and innovative structural approaches were adopted, and where these were sufficiently novel, they often proved remarkably successful and durable. An enduring aspect of a truly successful work of art has always been that it is sufficiently distinctive to be memorable, but sufficiently familiar to be recognisable.

Extensive testing was undertaken in advance, and fine tuned post release, to ensure that despite each consumer accessing their very own bespoke version of the film, it was in many key regards a common experience to a wide variety of users. A consumer might therefore watch a film in a film noir style, with a score in the style of Massenet, and their preferred female lead actress, with a conclusion that was clever, but emotionally unsatisfying, while their partner might have seen a film in a stylised Kabuki style, with a minimalist score, and their preferred male lead actor, with a conclusion that was emotionally resonant but clearly unlikely. However they had both clearly engaged in a very similar shared experience that could easily and pleasurably be discussed.

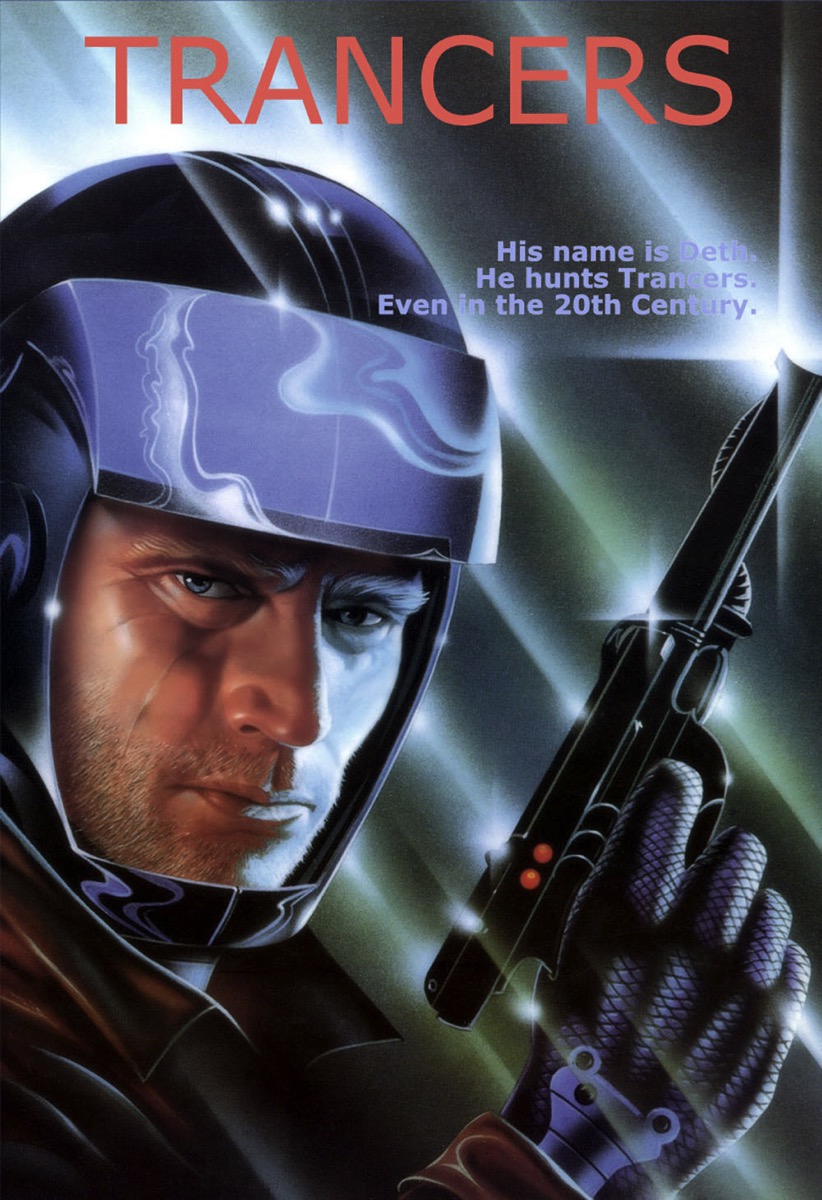

It was argued by some that this level of information load, and rapidity of pace, led to a focus on novelty and speed at the cost of genuine emotional resonance and meaning. It is however widely recognised that the consumption of culture is specific to the culture in which it is consumed. Just as we cannot truly recreate the experience of hearing a Beethoven symphony conducted by the composer, with a nineteenth century orchestra now, nor can we recreate the experience of watching a twentieth century classic such as Trancers with a cardboard box of stale popcorn sitting on a folding seat in a local fleapit.

Finally, the irresponsible disclosure of spoilers was rightly recognised as the major social challenge of the century. Initially it was thought that technology might be the answer. Rigid technology locks were applied so that narrative outcomes were not disclosed to people in advance. However public attitudes hardened and penal reform was clearly called for. In 2060 many countries introduced a mandatory prison sentence for blatant disregard of local spoiler disclosure conventions, the so called Spoiler Laws. Over the years average sentences for these offences were increased, and eventually they were one of the few offences to attract a near life sentence. However the death sentence for disclosure of spoilers was not yet widely present.

No comments:

Post a Comment