It was a lively day in the city, the air rich with the smell of spices, and the constant bustle of hawkers and stallholders all around us. My friend was up ahead, and I pushed through the crowd to catch up with her. Momentarily I lost sight of her, and I pushed on through the crowd, placing my hand on a back here, nudging between some shoulders there. I saw a door that I had never noticed before closing and caught it before it had fully shut.

In truth the other side of the door was nothing remarkable, little different from the bustling market space that I had left. There was another open market space, with the usual stalls, and up ahead a narrowing in the pillars to create a seeming corridor that shaded into darkness. I could see her mane of bright red hair for a moment but then she vanished into the darkness. I resolved to take my time, I had not noticed these stalls before and it was still early in the day.

The first stall was surrounded by a frantic crowd but when I got through I found that it held only a strange array of broken clock parts. Similarly the next stall was thronged but merely displayed a selection of broken glass, that had seemingly been dug up, the dirt still sticking to it. The further I ventured from the door, that I had passed without thinking, the more I noticed that which was at odds with all that I was familiar with. It seemed that everyone was wearing clothes that they had made themselves, they carried jute sacking or canvas, with which to wrap anything they might buy. A hurdy gurdy played a tune I did not recognise, the hot foods were with dipped in a sauce that glittered and glowed, when I looked at the seller, I noticed that his buttons were improvised pieces, sewn onto his coat, each a different size and shape, pottery punched with holes, stubby twigs.

Beyond a row of pillars was an expanse of round tables, the crowds were less dense, and despite the intensity of those sitting round the tables, it seemed more relaxed than the market space. I sat at one table, slowly realising that those round the table were gambling, I could not recognise the game, it involved strange tokens and playing cards that I could not recognise, their heads were down, as they studied the cards and tokens intently. One head was raised momentarily, and I recognised Simon an attorney from an office near where I worked. His eyes flashed brightly, he nodded in recognition and signalled me to come over. As I knelt down beside him, he welcomed me to the city of Voisin. Although his smile was bright and friendly and his tone welcoming, I could tell from his eyes that he was anxious for me. In a whispered voice he told me that in Voisin it is not done to wear a hat or scarf, and I should discard them as soon as possible. I could tell from his tone and seriousness that it was important not to react to any of this, to treat our conversation as mere friendly words, some chit chat, or commonplace remarks. I nodded that I understood, when it was clear that I did not. I made to stand up, and he beckoned to me one last time, I bent my head closer to him, he mouthed some words to me. The deeper you go, the more dangerous it gets.

I nodded to let him know that I understood, when, in truth, I did not. I left the table and wandered on, with the rough idea that the unexpected door that I had come through lay somewhere behind me. Without looking at anyone I slipped off my scarf and hat, and a few paces later dropped them in the gap beneath an empty table which was draped with a pale cloth.

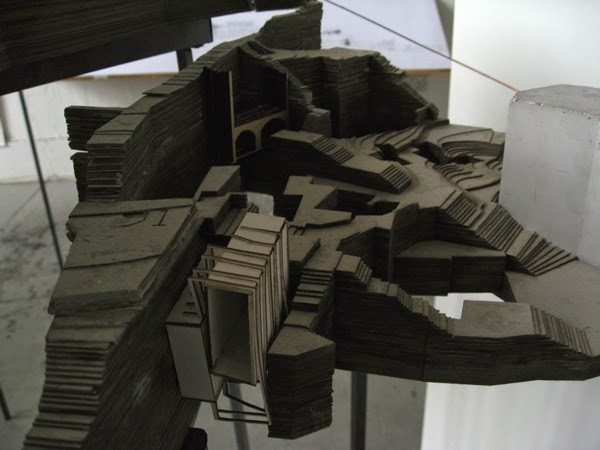

On looking around me, it was increasingly obvious to me that this was not the city that I had come from, although on first glance it looked the same. Things were made of painted cardboard, like the scenery at the theatre, canvas was stretched over straw, and crumpled paper filled gaps.

I resolved to …